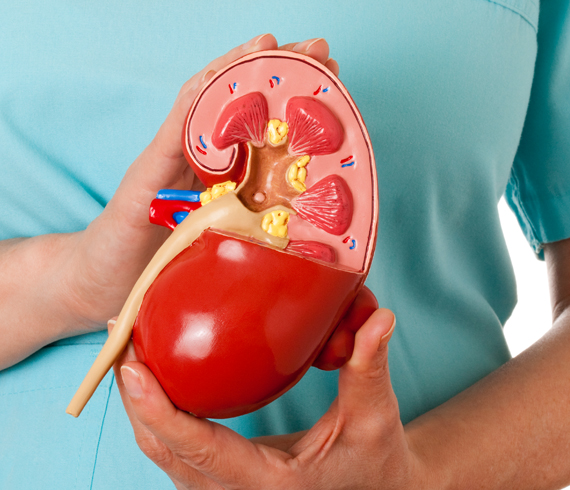

How kidney stones develop

The kidneys regulate levels of fluid, minerals, salts, and other substances in the body. Kidney stones form when substances in the urine (calcium, oxalate, and phosphorus) become highly concentrated and form crystals in the urinary tract.

Who is likely to develop a kidney stone?

The rate of people who develop kidney stones is increasing. In Australia an estimated 15% of men and 8% of women will develop kidney stones. A person who has suffered from one kidney stone is likely to develop others.

Factors known to increase the risk of kidney stones include:

- Dehydration

- Family history

- Genetics

- Diet

- Metabolic syndrome: A disorder diagnosed by co-occurrence of three out of five of the following medical conditions: obesity, hypertension, elevated fasting blood sugar level, high triglycerides and low high-density cholesterol (HDL) levels.

- Other medical conditions (Diabetes)

What are symptoms of kidney stones?

Many kidney stones are painless until they travel from the kidney, down the ureter, and into the bladder. Depending on the size of the stone, movement of the stone through the urinary tract can cause severe pain with sudden onset (renal colic). People who have kidney stones often describe the pain as excruciating. The lower back, abdomen, and sides are frequent sites of pain. Those who have kidney stones may see blood in their urine. Fever and chills are present when there is an infection. Seek prompt medical treatment in the event of these symptoms.

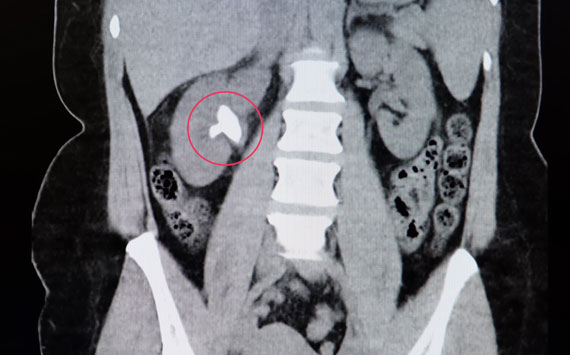

How are kidney stones diagnosed?

Kidney stones are diagnosed by excluding other possible causes of abdominal pain and associated symptoms. A CT scan confirms the diagnosis of kidney stones. Although the amount of radiation exposure associated with a CT scan is minimal, pregnant women and others may need to avoid even these low levels of radiation. In these cases, an ultrasound may be used to diagnose the kidney stone.

How can I prevent kidney stones?

Diet influences the rate of stone formation is one factor you can change to decrease your risk of new stone formation. Changes you can make, which have been scientifically proven to help reduce new stone formation are:

- Drink more water: Stones rarely form in dilute urine. To achieve this you need to drink enough water to make your urine look pale (about 2-3litres a day). You can consume other fluids in moderation (less than 500 ml/day). This includes coffee, tea, alcohol, diet soft drinks and fruit juice. You should avoid sugared soft drinks altogether.

- Reduce sodium (salt) intake: Salt causes the kidneys to excrete more calcium into the urine. More calcium in the urine results in high risk of stone formation.

- Avoid acid producing food: Kidneys normally re-absorb most of the calcium from the urine. Urine with a high acid load inhibits this re-absorptive process. The end result is more calcium in the urine, and again, higher risk of calcium stone formation.

- Increase Citrate intake: Citrate inhibits stone formation by making urine unfavorable for salt crystallization. Citrate is found in citrus fruits (lemon, oranges etc).

- Preference low GI food: Good control of blood sugars reduces stone disease.

- Ensure Vitamin D levels are normal.

- Maintain recommended calcium intake: For most individuals calcium from food does not increase the risk of stones. In fact the opposite is true. Calcium in the digestive tract binds to oxalate from food and keeps it from entering the blood, and therefore the urinary tract, where it can form stones

- Reduced animal protein: Meats and other animal protein—such as eggs and fish—contain purines, which break down into uric acid in the urine. High uric acid levels can promote the formation of both uric acid stones as well as calcium stones.

What is the treatment for kidney stones?

Treatment for kidney stones depends on the size, location, symptoms and the presence of complications associated with the stone.

| Treatment option | Suitable stones | Involves |

| Expectant | Small (<6mm) ureteric stones | Most small stones will pass without need for surgical intervention. After the diagnosis has been made and the initially required strong analgesia has worn off, the pain should remain settled. You should only require mild analgesia (panadeine, ibuprofen) and otherwise feel well. You need to be reviewed 4-6 weeks after the event to ensure the stone has past, this requires either repeat imaging or the appearance of the stone in your urine. |

| Ureteroscopy | Large ureteric stone | Stones that lodge in the ureter and do not pass are typically treated with ureteroscopy. A ureteroscope is a rigid or flexible instrument with a camera, light source and working channel. The light and camera allow the stone to be visualized while the working channel allows passage of a laser fibre. Laser is used to fragment the stone. |

| Pyeloscopy | Small stones in the kidney | As above the scope passes all the way to the kidney. |

| Percutenous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) | Large (Staghorn) stones in the renal pelvis | PCNL is a minimally-invasive procedure to remove stones from the kidney by a small puncture wound (up to about 1 cm) through the skin. It is most suitable to remove stones of more than 2 cm in size and which are present near the pelvic region. |

| External shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) | Small stones in the renal pelvis | ESWL uses sound waves or shock waves to break stones into small fragments that can pass spontaneously. It is performed usually as an outpatient procedure at prince of Wales hospital in Randwick. It may need to be repeated. |

| Nephrectomy | Stones in a poorly functioning kidney | If the kidney is poorly functioning the risk of recurrent stone formation can be high. Removing the kidney can prevent the need to repeat operations as well as clear infection. |

Complications that can occur with kidney stones

The two most common complications that can occur with kidney stones are renal failure and infection including severe infection (sepsis). The presence of either of these conditions necessitates urgency surgical intervention to ‘unblock’ the kidney. Definitive management (removal of the stone) however is reserved until you are medically safe.

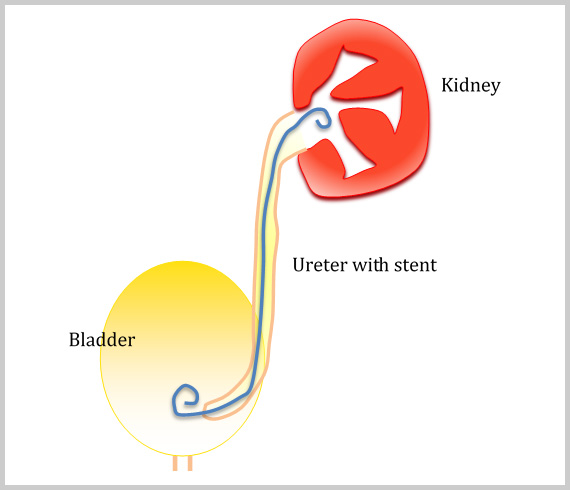

What is a ureteric stent?

A ureteric stent is a long, thin, hollow plastic tubes, 24-30 cm long and around 2 mm in diameter. It is placed within the ureter, the tube that connects and drains urine from your kidney to the bladder. Ureteric stents have a coil on each end which helps keep respective ends in the kidney and the bladder. They may also be called JJ stents or Double J stents. As a general rule, stents in people who have kidney stones can remain in place for up to 3 months. After this time the stent should be removed.

The role of the stent is:

- Ensure the kidney can continue to work normally thus prevents renal failure.

- Causes the ureter to dilate (stretch) making later endoscopic access easier and safer.

- Promotes passage of small stone fragments from kidney.

- Drains urine infected with bacteria.

It can be placed by two methods.

Retrograde insertion

The most common is in theatre. This is called retrograde insertion as the stent is past in the opposite direction to normal urine flow. Under an anaesthetic, following the normal urinary passages, the bladder is accessed and the stent is past over a wire to the kidney.

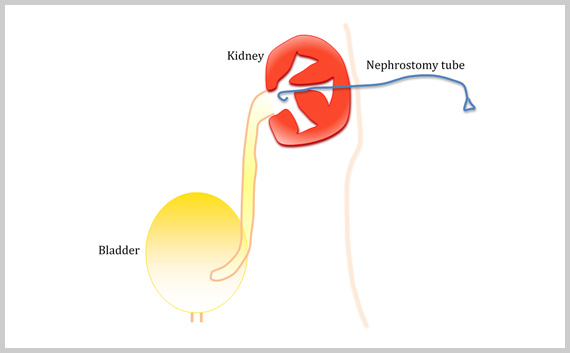

Antegrade insertion

A radiologist inserts an antegrade stent in the radiology department. It is usually done under local anaesthetic and is frequently a two-stage procedure. This approach is usually only done when a person is too sick for an anaesthetic or retrograde access is not possible. The first stage involves the radiologist making a small puncture through the back into the kidney. A small tube is then inserted to drain the kidney (nephrotomy tube). After a few days, the radiologist then feeds a wire down this tube and feeds the stent over the wire.

Symptoms associated with a ureteric stent

Most patients experience minor symptoms with a ureteric stent. These symptoms include:

- Frequency – Feeling the need to pass urine more often

- Urgency – An uncontrollable desire to pass urine.

- Incomplete emptying – Sensation that the bladder is not empty despite just passing urine

- Blood in the urine (haematuria) – Results from the lower end of the stent rubbing on the bladder. The blood may be particularly noticeable following physical activity.

- Discomfort in the bladder, kidney (loin) or genital area

- A feeling of fullness in the kidney on passing urine

Things you can do to minimise symptoms associated with a ureteric stent

- Increasing your fluid intake to around 2 litres of water a day, unless your renal physician or cardiologist has you on a fluid restriction.

- Simple analgesia: Take when required, includes tablets like nurofen and panadol

- Alkalise the urine: You can achieve this by taking Ural (up to 3 sachets a day) or drinking soda water

- Reduce your caffeine (coffee, tea, cola) and alcohol in take

What can I do with a stent in place?

You can continue to do all activities you would normally do, just be aware that physical activity may increase bleeding in some people.

KEY POINTS

- Kidney stones are common with almost 1 in 10 people developing a kidney stone.

- The most common presentation from kidney stones is when they move into the ureter causing severe pain (renal colic)

- Surgery may be required to remove the stones

- Not everyone is predisposed to forming kidney stones

- Those predisposed to forming stones can reduce the risk by modifying their diet.